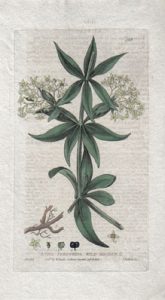

William Henry Perkin was the first chemist to synthesize a colour, -Mauveine, in order to mass-produce cutting down on an otherwise labour intensive, organic process. Later, in 1869 Perkin synthesized the vivid natural red dye Alizarin, an extract from the Madder plant, allowing for a more readily available and cheaper pigment for the dye industry. The patent for the synthesis was filed a day before Perkin by the German chemical company BASF, under suspicious and frustrating circumstances.

Mauve Dye

One such example resulted in British Patent No. 1984 for the synthesis of mauve dye in 1856. William Henry Perkin, undertook the project of trying to prepare artificially the anti-malarial drug, quinine, on his Easter vacation. He started with a simple waste product, aniline, from coal tar. He failed at synthesizing quinine but did produce a mysterious black powder. Given his training and curiosity he tried to discover what it was. He soon found that the powder dissolved in alcohol to produce a stunning purple color. Instead of discarding the solution, Perkin wondered if it might dye fabric. He found that not only did it color silk and cotton, but the color did not wash out with soap or fade when exposed to sunlight. Perkin built a factory to produce his mauve dye and it made him a rich man, allowing him to continue research on coal tar products. Using his accidental experimental results, William Henry worked out the synthesis of the red dye alizarin from anthracene, a component of coal tar. The value of these dyes is not limited to the textile industry. Researchers have found that bacteria can be stained and show up for microscopy when certain dyes are used. Tuberculosis and cholera bacilli were discovered using this technique.

The Coevolution of Industries and

National Institutions: Theory and Evidence

J. Peter Murmann

For thousands of years before the discovery of the first synthetic dye in 1856,

human beings all over the world dyed textiles, using coloring materials derived mainly

from plants and to a much smaller extent from such animals as mollusks. To extract, for

example, one gram of the natural dye Tyrian Purple from a tiny gland of the body of a

mollusk, 12000 animals were required. Because brilliant dyes that were resistant to wear

and tear were very expensive, the color of a person?s clothing would typically reveal

one?s socioeconomic status: common people tended to walk around either in undyed or in

dark single color linens whereas Kings and Queens at the apex of the social hierarchy

would show themselves in the most beautiful colors that the light spectrum has to offer.

The subsequent ?democratization of colors? was set in motion by the 18-year old William

Henry Perkin, who had enrolled as a student at the Royal College of Chemistry in

London and serendipitously discovered a purple coloring material in his test tube while

he was trying to synthesize quinine ? a substance that many an Englishman consumed as

a medicine to fight malaria on trips to the tropical possessions of the British empire.

Perkin abandoned his university career and together with his father and brother

opened up a year later the first plant that produced a synthetic dye in the world. They had

to overcome many production and marketing hurdles to commercialize William Henry?s

discovery. On the marketing side, Perkin & Sons was assisted greatly by the young

French Empress Eugénie who had been encouraged by the French court to wear the

newest patterns of the Lyon silk industry and the Parisian haute couture. In the second

half of 1857, the empress had become particularly fond of a new purple shade that had

been introduced by Lyon silk dyers. She created an haute couture fashion craze that, with

a season?s delay, spilled also into Great Britain and prompted British dyers and colorists

to overcome their resistance and use Perkin?s novel synthetic dye. Protected by a British

patent, Perkin & Sons made handsome monopoly profits. And within a few years, British

and French firms had introduced synthetic dyes spanning the entire color spectrum.

Contemporary observers were convinced that Britain was predestined to dominate

the global synthetic dye industry for decades. August Wilhelm Hofmann, for example,

who was the most distinguished organic chemist working in London at the time and

under whom Perkin had studied at the Royal College of Chemistry, wrote in his Report

(1863, p. 120) on the Chemical Section of the International Exhibition of 1862: ?[A]t no

distant date ? [Britain will be] the greatest colour producing country in the world; nay,

by the strangest revolutions, she may, ere long, send her coal-derived blues to indigo

growing India, her tar-distilled crimson to cochineal-producing Mexico and her fossil

substitutes for quercitron and safflower to China and Japan, and the other countries

whence these articles are now derived.? Although Britain and France were the leading

producers for the first decade of the synthetic dye industry, it was not Britain but

Germany that came to dominate the global market before World War I (WW I). Initially

copying British and French synthetic dyes, the German dye industry possessed by 1870 a

world market share of about 50% that continued to climb to about 85% at the outbreak of

World War I. At that point, the British and French global market shares had been reduced

to 3.1% and 1.2% respectively. Switzerland had become the second largest producer in

the world with 6.2% and the United States produced 1.9% of the world total (Reader,

1970, p. 258). In the year before World War I, synthetic dyes were Germany?s largest

export item (80% of domestic production was shipped abroad) and their production had

created a large amount of wealth for Germany because synthetic dyes, despite large price

decreases, remained a very profitable business for the large Germany producers. So

where is the puzzle?